Why I don’t call myself a skeptic any more

For much of my adult life, I’ve thought of myself as a skeptic. I strongly believe in the power of science as means to improve our lives…

For much of my adult life, I’ve thought of myself as a skeptic. I strongly believe in the power of science as means to improve our lives and understand the world, I do not believe in a realm beyond the material and I have a deep seated commitment to making sure that the things I believe about the world are true. None of that has changed, but I no longer call myself a skeptic and I would like to talk about why.

What is skepticism?

Modern popular skepticism emerged as a political and philosophical movement towards the end of the 20th century, taking off in the mainstream in the early 00s. Skepticism in this sense values an empirical approach to truth and takes as its enemy various kinds of untrue beliefs; religion, alternative medicine, conspiracy theories and superstition. For skepticism, social harm arises from a lack of critical thinking; people lack the tools to distinguish truth from falsehood and thus form false beliefs that lead to harm.

A vast, disparate network of pop science books, blogs, podcasts, gatherings in pubs and social clubs have formed around skepticism. The people who participate in this community view themselves as skeptics. For the skeptics, skepticism often forms a central plank of their identity and how they see the world. They are an in group, distinguished from the out group by their rationality and unflinching commitment to evidence.

Types of people

[A] certain kind of human seen as “scientifically rational” is culturally made up in relation to the Other (Hacking 1995). This Other is either trusting “irrational things” (such as religion, traditional knowledge, post-truth) or simply not thought of as being subjected to scientific rationality or technological development (at all). Frequently, the latter depends on where the person is situated in the world. The practice of science, and the science-literate person, is thought of as connected to a certain place: the West. — Malin Ideland, Science, Coloniality and the “the Great Rationality Divide”

Post-colonial studies and critical race theory have explored the concept of “rationality” and “science” as being properties attached to certain types of people, in the context of race, this constitutes the idea of a scientific, rational, progressive West as opposed to the rest of the world and the types of people that originate from outside of the West. Certain types of people are viewed as rational subjects, as reliable sources of knowledge. This phenomenon has been called hermeneutic or epistemic injustice (I will use the latter here because it’s easier to spell). The feminist author Sara Ahmed has written extensively on this topic.

The concept of epistemic injustice has uses outside of race; women are viewed as irrational, mad people are viewed as unreliable narrators. Trans people, as a heavily psychiatrised population, are viewed as mad women (regardless of our genders), as fundamentally incapable of producing legitimate knowledge about the world. The issue is not what we say or what we do, but type of people we are, the value judgement of rationality or irrationality then being projected on to our words or behaviour.

In light of this, skepticism as an identity becomes deeply fraught. While there is nothing in valuing evidence or critical thinking that must inherently be racist, sexist, ableist, transphobic etc., in a society that already rife with prejudice about which categories of people are capable of embodying this sort of rational enquiry, a political project that identifies separate rational and irrational types of people is necessarily very vulnerable to falling into deep seated bigotry. In the next two sections I will be looking at two prominent skeptical figures and showing how this epistemic injustice appears in their work.

Did Muhammed fly to heaven on a white horse?

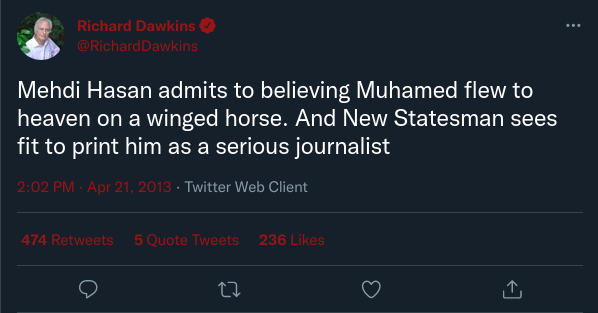

In 2013, prominent atheist and skeptic Richard Dawkins expressed his disgust at liberal magazine the New Statesman publishing work by Muslim journalist Mehdi Hasan on the basis that Hasan holds Muslim beliefs. Dawkins argues that Hasan, as a Muslim, is not a type of person who can be relied upon as a source of knowledge. Implicit here is the clearly racist assumption that the almost 2 billion Muslims in the world, mostly people of colour and mostly in the global South, are fundamentally irrational people, not worthy of being reasoned with or taken seriously.

Dawkins has also intervened in the trans “debate”, notably announcing that he had signed the “Women’s Declaration on Sex Based Rights.” Other authors have spent a great deal of time explaining that this document is deeply transphobic and counter to most understandings of human rights, however, what is most notable for my purposes is the tension between Dawkins’ role as a supposed educator and advocate for science and his signature on a document that calls for the restriction of research that the authors find offensive.

“medical research which is aimed at enabling men to gestate and give birth to children is a violation of the physical and reproductive integrity of girls and women, and is to be eliminated as a form of sex-based discrimination.” — Declaration on Women’s Sex-Based Rights Section 3)a)

Dawkins himself has issued statements at odds with such an argument.

“The only really deep reason people have for objecting to such a thing is that it offends some deep-seated sense — what’s been called the `yuk’ reaction. It’s irrational” — Dawkins on human cloning

Indeed, signing a document explicitly opposed to surrogacy in all forms is at odds with currently existing cloning technology altogether, which necessarily requires a surrogate to carry a cloned embryo to term.

While I cannot know for certain whether Dawkins read the declaration in full before signing, one could be forgiven for thinking that he simply assumed that any document that attacked advances in transgender rights must be rational and scientific.

The curious affair of Alan Sokal

Alan Sokal is a physicist whose most widely known work is getting a bad paper published. The Sokal Affair is a notorious incident in the “science wars” of the early 1990s, wherein Sokal was able to get a paper making a number of absurd claims published in a humanities journal, from this we are supposed to conclude that the entire field of the humanities is worthless. The significance of this hoax relies largely upon the lack of public understanding that the publication of a single journal article is not an endorsement from an entire field and that, with enough effort, you can get almost anything published. It seems odd that we are not similarly called to dismiss the entirety of science on the basis of the many, far more consequential, frauds that have occurred in scientific literature. Nevertheless, the hoax paper secured Sokal a place as a celebrity of the then nascent skeptic movement.

Recently Sokal has chosen to intervene in the public conversation on sexual orientation and gender identity conversion efforts (SOGICE or conversion therapy), with a submission to the UK government’s consultation on a ban on conversion therapy. In his submission, Sokal outlines the common “Gender Critical” argument on conversion therapy, essentially that sexual orientation conversion therapy and gender identity conversion therapy are fundamentally different, with the latter being poorly defined. Sokal additionally makes a number of factual claims, including that:

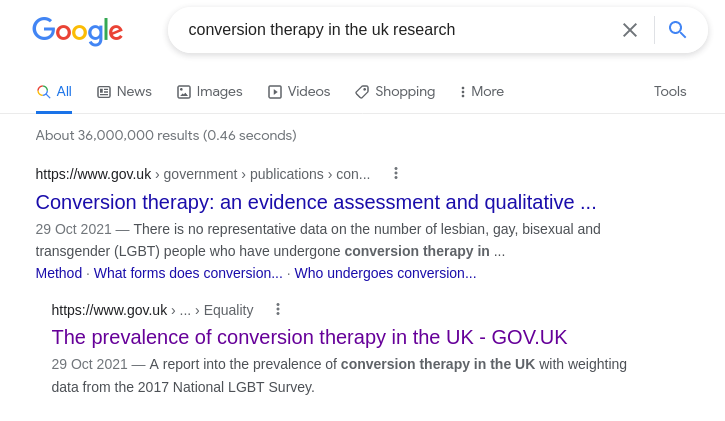

- “It is not clear whether conversion therapy with respect to sexual orientation is practiced today to any significant extent.” Sokal seems to claim that either no evidence exists for the prevalence of conversion therapy in the UK or that the government has failed to consider the evidence on this stubject. However, extensive research on the prevalence of conversion therapy exists and summaries of this evidence can be easily found on the UK government website, with around 1 in 50 LGB people and 1 in 25 transgender people having been subjected to efforts to render them heterosexual or cisgender. While truly representative survey data can be difficult to produce, efforts towards this can provide us with a picture of the scale of the problem.

- “The concept of “gender identity” […] is notoriously ill-defined and ambiguous.” On this subject, Sokal cites a two texts, Kathleen Stock’s Material Girls and a Quillette article by Stock outlining essentially the same argument. Sokal uses this claim to argue that any resulting ban on gender identity conversion therapy would be similarly ill-defined and thus counter to norms of human rights. Sokal does not appear to have engaged with any serious scholarship of gender identity, nor to have read the glossary on the gov.uk website connected to their summary of the evidence on conversion therapy, which defines gender identity as “A person’s internal sense of their own gender.” This definition does not depend on any particular etiology of gender, where it is necessarily innate or bound to “gendered souls” as Sokal implies.

- “the situation is completely different with regard to gender identity [as opposed to sexual orientation].” Any serious look at the history and present day reality of conversion therapy would show that both sexual orientation and gender identity conversion efforts are often carried out in the same environments by the same people with very similar outcomes (little evidence of persistent change and a great deal of evidence for long term psychological harm). Infamous conversion therapy body NARTH, a US professional body for conversion therapists that has been prominent in campaigning against gay rights and has previously published material arguing that the Black, gay and women’s civil rights movements were “destructive”, recently rebranded itself as the Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity (ATCSI). ATCSI has claimed that “there are significant psychological, medical and societal risks associated with attempts to alter someone’s biological sex through hormone therapy or sexual reassignment surgery” on it’s Transgender page, providing resources for conversion therapy as an alternative. It is simply incoherent to claim a clear division between sexual orientation and gender identity conversion therapy given the most basic of research.

In short, Sokal shows a fundamental lack of curiosity about the evidence and material reality of conversion therapy, while making very strong claims and public interventions on the subject.

Skepticism without skeptics

What can be seen in my two case studies above is not a shortcoming of a skeptical approach. In fact a truly skeptical approach, taking Muslim writers’ arguments on their own merits, closely reading things before committing to them and taking the time to research a topic before wading into it would have avoided this. However, both Dawkins’ and Sokal’s errors are examples of how a skeptical identity can form a barrier to skeptical thinking.

If we want to avoid falling into the trap of perpetuating epistemic injustice and making false claims about marginalised groups, we have to stop trying to be skeptics and instead be a little more skeptical about our own standpoint.