Sex, gender and breast cancer

So last week I published a piece on trans health and cervixes and in that piece I offhandedly mentioned an example of why being registered…

So last week I published a piece on trans health and cervixes and in that piece I offhandedly mentioned an example of why being registered under our assigned at birth sex isn’t a workable solution for trans people; breast cancer for trans women. I wanted to expand on this a little bit.

The risk

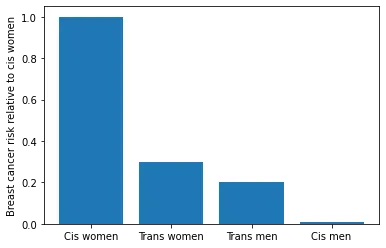

A 2019 paper by Christel J M de Blok et al., published in the BMJ, explores breast cancer risk in trans people on HRT. The study looked at 3,489 transgender people on HRT (about two thirds trans women, with the remaining third trans men) and compared their risk of invasive breast cancer to baseline rates in cisgender men and women. Below is a bar chart showing the relative risks reported in the paper.

The relative risks for trans women and trans men were 0.3 (confidence interval 0.2–0.4) and 0.2 (confidence interval 0.1–0.5) relative to cisgender women. This means that the risk in trans people on hormone therapy is lower than that of cis women, but comparable, and much higher than that of cis men. Overlapping confidence intervals suggest that we cannot conclude from this data whether there is a clinically relevant difference in risk for trans women and trans men.

The practical implications

The study concludes that the existing practice in the Netherlands (where the study was carried out) of using the same breast cancer screening procedure for both trans men and women as for cis women is reasonable. This compares poorly with NHS policy, as described in a 2019 PHE leaflet, where which forms of cancer screening trans people are sent regular reminders for is governed not by our risk, but by which sex we are registered as at our GP.

NHS systems are designed with the assumption that all patients are both cisgender (not trans) and dyadic (not intersex). For trans (roughly 200,000–500,000 people in the UK) and intersex people (roughly 380,000 people in the UK), our healthcare needs may differ from those of the majority of the population, healthcare systems that are not designed with this in mind necessarily discriminate against us, leading to poorer quality of preventative care.

In the case of breast cancer, as with cervical cancer, better healthcare outcomes for trans people could be secured simply by adding fields to databases used by GPs to send screening reminders that specify whether a patient has the relevant body parts. The failure of the NHS to do this instead of producing leaflets informing us of their discriminatory policy constitutes a form of systemic, hidden violence against us.