Cass and social transition: What does the evidence tell us?

The team behind the Cass review recently published an FAQ seeking to clarify certain claims being made about the review. Speaking against…

The team behind the Cass review recently published an FAQ seeking to clarify certain claims being made about the review. Speaking against the widespread claim that the review recommends forbidding social transition for children and young people without medical supervision, the FAQ states:

The Review has advised that a more cautious approach around social transition needs to be taken for pre-pubertal children than for adolescents and has recommended that:

“When families/carers are making decisions about social transition of pre-pubertal children, services should ensure that they can be seen as early as possible by a clinical professional with relevant experience.”

Parents are encouraged to seek clinical help and advice in deciding how to support a child with gender incongruence and should be prioritised on the waiting list for early consultation on this issue. This should include discussion of the risks and benefits and the voice of the child should be heard. It will be important that flexibility is maintained, and options remain open.

I’d like to unpack the basis of this call for caution and the evidence that Cass uses to support it.

In the clarification section under this FAQ answer, Cass states that “it is possible that social transition in childhood may change the trajectory of gender identity development for children with early gender incongruence.” In other words, Cass is claiming that part of the reason to be “more cautious” about social transition for prepubertal trans children is that this may make them more likely to continue to be trans later in life. My immediate reaction to such a claim is, bluntly, so what?

At the heart of Cass’ expressed concern that social transition may “change the trajectory of gender identity development” is, in my opinion, an example of what the academic Cal Horton has called “cis-supremacy” in the Cass review. Unless you regard being trans as a worse outcome than being cis, there is no reason to be “cautious” about allowing trans children and young people to engage in self-directed exploration that might make them more likely to be trans adults. Having said that, given the prestige of the Cass Review Final Report and the extent to which it has been lauded in the press as a truly evidence based document, how strong is the evidence on which Cass makes this claim? And what is she actually claiming?

Much of this topic is covered on pages 162–163 of the Cass Review Final Report under the subsection “Gender identity outcomes.” It’s important to keep in mind the context that much of what Cass discusses as childhood social transition refers exclusively to pre-pubertal children, with older children refers to as adolescents.

On the topic of gender identity outcomes for childhood social transition (pg 162), Cass considers two studies, Olson et al, 2022 and Steensma et al, 2013.

Olson et al. 2022 looked at a sample of 317 children who had socially transitioned between the ages of 3 and 12 and looked at whether they were still trans 5 years later. Of the sample, 97.5% identified as trans (including nonbinary identities) after 5 years. However, this study had no comparator group of children who had not socially transitioned and therefore cannot necessarily tell us whether social transition was the reason that these kids were still trans.

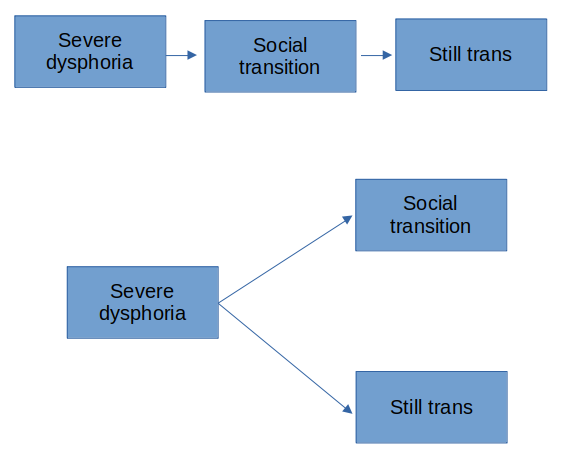

Steensma et al. 2013 looked at 127 adolescents who had been referred to gender identity services before the age of 12 and attempted to identify factors that distinguished between “persisters” (still trans) and “desisters” (no longer trans). As Cass points out in her report, this study found that, for AMAB children only, social transition was associated with still being trans. However, in this study severity of childhood gender dysphoria was even more strongly associated with “persistence” than social transition and was, itself, associated with social transition. This makes it difficult to conclude from these data that childhood social transition, of itself, causes trans kids to become trans adults.

When we have three variables in a dataset, all of which are correlated with each other, there are a number of different models of causality we can consider. For example, does severe dysphoria lead to greater likelihood of social transition, which leads to still being trans or does severe dysphoria lead to both a greater likelihood of social transition and a greater likelihood of still being trans? I would be more inclined to assume the latter; the greater the degree of discomfort a child has with their assigned sex, the more likely they are to push through the many, many barriers to childhood social transition and to remain uncomfortable with their assigned sex.

So, if, as Cass states in her report, “it is not possible to attribute causality in either direction” (pg 163) between social transition and trans kids becoming trans adults based on studies on actual trans children, on what basis does Cass claim that “it is possible” that such a link exists? For this, Cass turns to data on intersex people. Most intersex people are not trans, just as most perisex (non-intersex) people are not trans; they identify as the sex they were assigned at birth. From this Cass concludes that “sex of rearing” (i.e. assigned sex) powerfully shapes gender identity. I don’t necessarily agree with this claim as applied to birth assigned sex. I disagree with the equivalence Cass draws here between social transition and assigned sex, however.

Sex assignment is not merely a parenting decision, it is a social process in which people are placed into categories whose borders are enforced by a great deal of social violence. No cis child has ever been kicked in the head by another child for the mere fact of conforming to their “sex of rearing.” It is ludicrous that Cass attempts to act as if living as a trans child is uncontentious with respect to gender expression in the same way that living as a cis child is; that growing up in a particular gender is experientially the same for trans and cis kids.

Cass is clearly aware of the tenuous nature of her claims here. She limits herself to saying that it is “possible” that social transition shapes gender identity development in the way that she suggests. Based on the evidence Cass uses, this is true only in the sense that it is possible that social transition has no effect whatsoever on gender identity development. For all that we are told that the Cass Review Final Report is the last word in evidence on trans children’s lives, the basis for some of its recommendations is pretty shaky.

In the context of such shoddily evidenced claims based on transphobic assumptions, I can hardly blame a lot of trans kids and their families if they’re a little nervous about exactly what kind of “support” Cass wants them to have.